Efforts to Indigenize and decolonize university curriculum has increased in Canada. UBC is playing an active role in the process in British Columbia through its Indigenous Strategic Plan, which lays out priorities and pathways, and the many funding opportunities throughout the university for projects that support this vision. The Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences embarked on this journey by supporting the inclusion of more Indigenous-specific teaching hours in the undergraduate PharmD curriculum and the work of the UPROOT team. By embracing a Two-Eyed Seeing approach and building strong relationships with Indigenous partners and students, the UPROOT team is helping to change how Pharmacy is taught, and what it means to be a pharmacist practicing cultural safety.

Widening the scope of pharmacy teaching and learning

“Pharmacy is deeply rooted in colonial and Western values, with evidence-based medicine the primary model we use for teaching,” explains Assistant Professor of Teaching in the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences and co-principal investigator of UPROOT Larry Leung. “It can also be seen as a transactional approach to care provision.”

The way pharmacy is taught in universities often reflects this approach, which leaves little room for other perspectives on care, even when they exist locally. Indeed, Indigenous ways of providing care remained mostly absent from UBC’s pharmacy curriculum for a long time, both in content and representation.

“When we started in the Pharmacy program, there was very little Indigenous student representation,” shares Lindsay Ellefson, a fourth-year student in the undergraduate program and a member of UPROOT. “We had some cultural workshops and other activities, but there was little Indigenous content in the curriculum.”

This learning context can create limitations for future pharmacists, who are often the first-care point of contact. “In many places, you can usually find a pharmacy or access a pharmacist, even in rural or remote areas,” describes Assistant Professor of Teaching in the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences and co-principal investigator of UPROOT Jason Min. “There’s a greater emphasis and recognition now on the different clinical skills that we can offer.”

As a result, applying a Westernized perspective to an Indigenous context can lead to challenges for new pharmacists trying to deliver culturally safe care and support other forms of traditional healing, as Larry mentions. “A lot of these biased practices we see today were built directly into the curriculum and can be very challenging to unpack.”

“When Larry and I graduated through the UBC program, neither of us had any exposure, knowledge or training on Indigenous health, or even what terms like cultural safety and humility mean,” remembers Jason. “We realized there was a gap in learning that we felt we should have been better prepared for, which is how we became interested in this process as non-Indigenous educators.”

After spending over 10 years building relationships and traveling to Indigenous communities, their team of Indigenous community partners, students and knowledge experts received a three-year Large Teaching and Learning Enhancement Fund (TLEF) grant to design two courses within the Pharmacy curriculum by including more Indigenous perspectives, representation and approaches into the Entry-to-Practice PharmD program.

Using a Two-Eyed Seeing approach

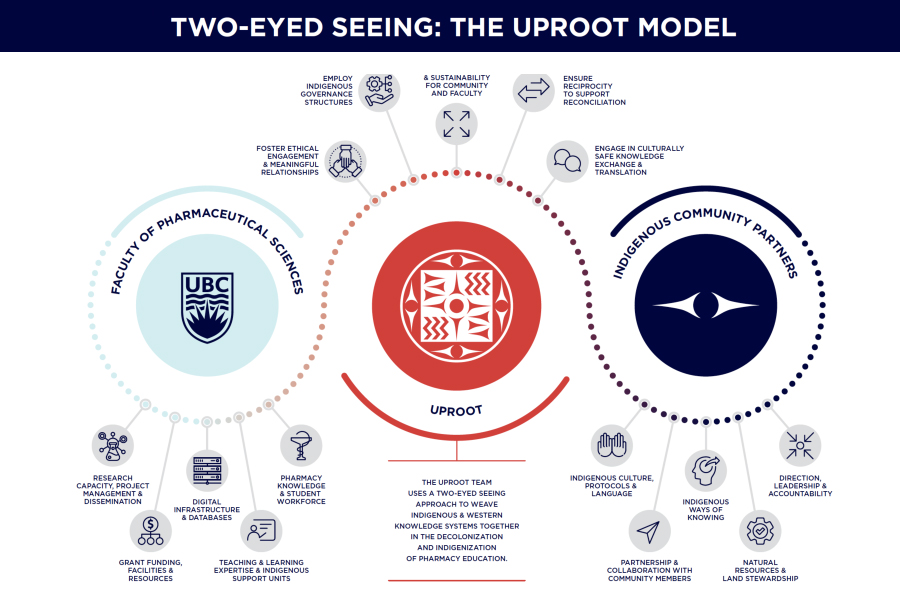

At the core of the project is the UPROOT approach, which comes from the what, how, and why the team is doing this work. Comprised of faculty members, self-identified Indigenous students and external Indigenous partners, the team’s objective is to uproot colonial processes and systemic barriers in an effort to support decolonization and indigenization of pharmacy.

“When given the opportunity, I was more than happy to be a part of the UPROOT project,” explains Patricia Bobb, an Indigenous Licenced Practical Nurse living and working for the Lil’wat Nation in British Columbia. “As an Indigenous person, and as a nurse, I was happy to have a place where I knew my voice would be heard.”

Indigenous Knowledge and Natural Science Lecturer for the UBC Faculty of Forestry, Dr. Sm’hayetsk Teresa Ryan, who was involved in the early steps of what became UPROOT, emphasizes the team’s unique approach as its main strength. “It endogenized context from their own personal experience, other practitioners working directly in First Nations communities, and Indigenous people – including those in communities – to evaluate the efficacy of the training. Larry and Jason respected my contribution as an academic Aboriginal woman, along with our other colleagues.”

Indigenous student involvement was also crucial to Larry and Jason, who were looking to include their perspectives in the project as well. “The UPROOT team was looking for self-identified Indigenous students to give feedback on the curriculum they were creating,” remembers Lindsay Swanson, another fourth-year student in the undergraduate program and member of the UPROOT team. “Larry and Jason created a safe space for us, which encouraged us to be more involved.”

A key pillar of UPROOT is a modified version of the Two-Eyed Seeing model, an approach of inquiry and solutions in which people come together to view the world through an Indigenous lens with one eye, while the other eye sees through a Western lens. Used as the project’s compass, it weaves Indigenous and Western knowledge systems together by combining the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Science research capacity, grant funding and digital infrastructure with Indigenous community partners’ way of knowing, leadership and culture to create a unifying experience that benefits everyone.

“The Two-Eyed Seeing model is in everything that we do,” Jason asserts. “We use it to build all the deliverables and outputs we produce, and it is the founding principle of our relationships with Indigenous partners and students.”

More importantly, as Larry explains, the model acknowledges that both sides can learn from one another and reach positive results, but that a specific and large emphasis must be placed on uplifting Indigenous voices. “Our use of the Two-Eyed Seeing model acknowledges that we, as UBC faculty members, offer certain skills and knowledge, just like our Indigenous partners offer theirs. The number one thing about our approach is that it can deliver outcomes that are reciprocal and mutually beneficial, so that it doesn’t only benefit the academic metrics of success, but also places direct and measurable benefits for our Indigenous partners.”

This change in approach was well received from students, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, who welcomed learning other ways to provide care for everyone.

“This model allows for both perspectives to be seen equally, without one being considered superior to the other,” Lindsay S. explains. “It’s about understanding and appreciating both sides.”

Following this approach, the team created a collaborative and reciprocal experience that went beyond curriculum redesign.

Creating meaningful outcomes through relationships

A central aspect of this Two-Eyed Seeing model is to foster ethical engagement, meaningful relationships, and to welcome different ways of teaching and learning while ensuring reciprocity in the projects and curriculum developed for both pharmacy student learners and community members. More importantly, it allows students to be involved and gain experience on the field when working on community projects.

“Jason and a group of students are assisting me on a diabetes-focused project,” explains Patricia. “We have developed a small curriculum to provide diabetes education that is culturally safe and appropriate for community members. Working as a team, we learned a lot from each other as we all had different ideas and experiences to share.” Moving forward, this project will benefit the community with customized diabetes education.

Another example of this approach is a Traditional Health and Medicine project to preserve and revitalize traditional medicines knowledges. For this project, the team used the Two-Eyed Seeing approach with Indigenous knowledge keepers to decide how multiple viewpoints would benefit from the work, which resulted in different versions of the resource that can be shared both orally and visually.

“We developed a redacted version of the resource for our students that did not include any privileged knowledge,” Jason details. “In addition, we developed a complete and fully accessible version of the resource that is meant to stay within the Indigenous communities. They are now using it in their health centers and their schools as a teaching aid.”

“That’s Two-Eyed Seeing in action,” echoes Lindsay S. “It allows both perspectives to be seen equally and to be as beneficial to students as it is to Indigenous partners.”

Another example of UPROOT’s desire to include more Indigenous perspectives in the Entry-to-Practice PharmD program is the Indigenous Advisory Committee, which bridged the two approaches. “Relationship building is a critical key to decolonizing the institutions that have had persistent negative impacts on First Nations and Indigenous people,” explains Sm’hayetsk. “Larry and Jason’s diligence in following through with their vision is evidenced in the success of the program.”

Student involvement was critical to Larry and Jason, who considered Lindsay E. and Lindsay S. as equal partners in the project. This trust encouraged them to create an Indigenous student advisory sub-committee, which soon evolved into a collegium that became a central part of the UPROOT team.

“With the collegium, we were able to create a safe environment for self-identified Indigenous students and offer support for practicum funds to help them travel to remote locations,” explains Lindsay S. “We also set aside some funds to help students accomplish community engagement efforts, and we organized cultural immersion activities for Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.”

“We worked with the Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre in Squamish, BC, to host interactive workshops,” Lindsay E. continues. “We hosted a dream catcher making workshop where an Indigenous expert came and brought all the necessary materials to make them, while also sharing background knowledge on their importance and cultural significance.”

Building and maintaining relationships with Indigenous partners is the backbone of the program’s success. To achieve this, Larry and Jason went to great lengths to prioritize the connections made throughout the project over typical academic pursuits and outputs.

“What we mean by this is that we will not pursue anything that our partners are not comfortable with,” Larry explains. “There were numerous occasions where we dropped grant projects or curriculum changes to respect their perspectives. This was very important to us, because Jason and I are not Indigenous. Therefore, we need to trust our partners on what can be shared and what needs to remain within Indigenous communities.”

“The collaborative process was very inclusive,” details Patricia. “We all have a voice, participate in discussions, and help strategize the best ways to move forward with our projects. This could mean community visits, team meetings or phone calls as often as needed.”

This commitment extends beyond co-developing courses for Larry and Jason, who have adopted Ownership, Control, Access and Possession principles set by the First Nations Governance Centre in Canada.

“The data now belong to our partners,” Jason echoes. “They have full control over it, which helps strengthen our existing partnerships and create more, because our partners can tell how much we care about this.”

We gratefully acknowledge the significant contributions of the UPROOT team members:

- Indigenous Curriculum Advisory Committee – Patricia Bobb, Doreen Hopkins, Teresa Ryan, Glenda Phillips, Carolyn MacKinnon, Lindsay Ellefson, Lindsay Swanson

- Indigenous Student-led Subcommittee – Olivia Burton, Manrubby Dhillon, Lindsay Ellefson, Caylee Lawrence, Lindsay Swanson, Brandon Whitmore, Emma Young

- Undergraduate Academic Assistants – Tuskonne Blais, Tia De Groot, Brina Kim, Brittany King, Jessie Li, Nailah King-Hopkins, Idaylia Swanson, Brandon Whitmore, Emma Young

Now at the end of the three-year Large TLEF project, the team is proud of all the work done by everyone, and the relationships created throughout the UPROOT project.

“What I’m the proudest of at the end of these three years is that our partners want to continue to work with us,” Jason emphasizes. “They are happy about the curricular advancements we have made, and they feel invested in the growth of future pharmacy students and pharmacists.”

they feel invested in the growth of future pharmacy students and pharmacists.”

For Larry, the number of students who connected with Indigenous partners through the curriculum redesign stands out. “I’m very proud about the number of students that have been involved, which has been far bigger than our team anticipated.”

“I’m really proud of the overall growth of student involvement in the project,” echoes Lindsay S. “To think that we went from being a part of the Indigenous Advisory Committee providing input, to now basically leading our own projects is incredible.”

As for the future, everything is in place for the UPROOT project to not only be sustainable, but thriving, as Lindsay E. explains. “Right from the start, Jason and Larry emphasized the need for sustainability and longevity with the project. We didn’t want these cultural immersion activities to disappear after one year.”

While hoping that the new courses will increase interest in Pharmacy by Indigenous students, the team thinks the curriculum is going in the right direction. “I don’t think there is anything wrong that we teach Western perspectives, but the scope should be broader so that pharmacists can have a more holistic view of health,” Jason concludes. “That’s part of how we can change the culture around Pharmacy, so that people don’t think of us as dispensing medication only.”

“The committee members worked very well together in providing advice and guidance in developing the program and curriculum,” Sm’hayetsk highlights. “Good hearts, good minds, and amazing progress, one step at a time.”

Lindsay E. and Lindsay S., who are about to graduate and become practitioners, will continue to take part in the project and cannot wait to use their broader knowledge on the field. “It’s an ongoing learning experience, but we do feel better prepared now,” summarizes Lindsay S. “Even though, of course, there’s still a lot more that we can do.”

“The UPROOT project initiative is an amazing way to approach decolonizing the way pharmacy is taught,” Patricia concludes. “Other programs and institutions need to recognize the importance of the work that is being done here.”